Kostas Karyotakis

(1897-1928), ou le suicide d’un buveur d’eau. À trente ans, il essaie en effet de se noyer. En vain. Il écrit, avant de réussir sa mort en se tirant une balle en plein cœur : « Je

conseille à tous ceux qui savent nager de ne jamais se suicider en se jetant à la mer. Pendant dix heures, je me suis battu contre les vagues. J’ai avalé une quantité énorme d’eau. »

Ses idées suicidaires lui vinrent peut-être de la syphilis dont il était affecté. Cela dit, il écrivit une œuvre pessimiste, pleine de désillusions, marquée par l’expressionnisme et le surréalisme. Sur la photo qui le représente suicidé, sa tête repose bizarrement sur un canotier.

(Impatienta doloris)

Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972) fut un des grands écrivains du XXè siècle, premier prix Nobel japonais (en 1968).

Ses œuvres les plus connues internationalement sont ses romans comme Pays de neige, Le Grondement des montagnes.

Il ne se remit peut-être jamais des fiançailles rompues sans explications par celle qu’il aimait, Itō Hatsuyo.

En 1970, il est bouleversé par le suicide de son disciple et ami Mishima. En 1972, il est hospitalisé pour une appendicite. Il ne recouvrera jamais vraiment la santé. Il se suicide au gaz (et non par seppuku) à 72 ans.

(Tædium vitæ).

Destin très étonnant que celui d’Alexandre Kazakov (1891-1919). Il fut avec Guynemer l’un des plus grands aviateurs de la Première Guerre mondiale. En 1914, il sert d’abord dans la cavalerie avant d’intégrer l’école de pilotage de Sébastopol. Il abat de très nombreux avions allemands, parfois de manière un peu rustique, comme quand il accroche un grappin à l’avion ennemi. Lorsque Nicolas II abdique, c’est la débâcle dans l’armée russe. Kazakov se replie avec son unité et remporte sa dix-septième et ultime victoire le 13 septembre 1917. Lorsque la révolution bolchévique éclate, la guerre contre les Allemands s’arrête. Kazakov rejoint les Russes blancs en lutte contre les bolcheviques. Il participe à la prise d’Arkhangelsk aux côtés des Anglais venus lutter contre l’armée rouge. Les Britanniques considérant que la victoire bes rouges est inévitable, il cesse d’armer les troupes blanches. Écœuré, le 3 août 1919, Kazakov décolle de la base de Berezniki et se laisse tomber comme une pierre.

(Pudor)

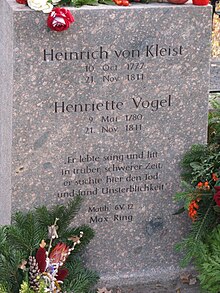

Génie foudroyé, Heinrich von Kleist. Pas facile d’être romantique en ce temps-là. Il aime une femme qui souffre d’un cancer incurable. Elle est mariée, bien sûr, sinon ce serait trop banal. Lui et Henriette s’installent dans une pension où ils rédigent leurs dernières volontés. Dans la bonne humeur, au cas où. Avant cela, en 1803, il s’était engagé secrètement dans l’armée française avec l’espoir de mourir en combattant contre les Anglais.

En 1810, il espère une coalition entre la Prusse et l’Autriche contre Napoléon. Il écrit alors Le Prince de Hombourg en l’honneur de la famille de Hohenzollern.

Il adresse à Henriette les Litanies de la Mort. Ils se donnent rendez-vous à Wannsee, où ils se donnent la mort : Kleist tue Henriette puis retourne l'arme contre lui.

On peut lire sur sa tombe un vers tiré du Prince de Hombourg : « Nun, o Unsterblichkeit, bist du ganz mein » (Maintenant, ô immortalité, tu es toute à moi !).

Avant de mourir, il avait écrit à une parente : « J’ai trouvé une amie dont l’âme vogue comme un jeune aigle [son nom, Vogel, signifie oiseau en allemand]. […] Tu comprendras que mon seul souci soit de trouver, en même temps que ma joie, un abîme assez profond pour m’y précipiter avec elle. »

(Impatienta Doloris).

/image%2F0549186%2F20210506%2Fob_74c4ce_capture-d-ecran-2021-05-06-a-07-56.png)